In today’s digitally-driven B2B marketing environment—one which offers buyers easy access to access to an array of information and myriad opinions—companies no longer control exactly where or when customers or prospects encounter their brand. And with more buyers engaging in more self-guided interactions, it’s safe to say that all B2B brands are digital brands, whether they like it or not.

These realities create an imperative. Business leaders need to understand what matters most to the people who matter most to them, then build a digital brand that organizes ideas and information to meet their audiences’ needs.

The Urgent Matter of the B2B Brand Website

A B2B company’s website is the hub of its digital brand. So it makes sense that the state of the site is usually the most urgent and acute pain point for B2B marketers. For companies going through a rebranding initiative, the website often serves as the first real application of the new verbal and visual platform. And while this can provide an agile testing ground for the strength and flexibility of the new brand, it can also unearth some important brand gaps.

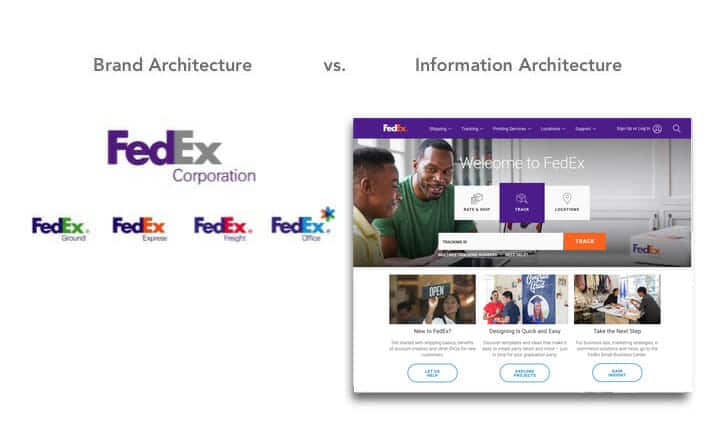

For example, one increasingly gray area for B2B marketers is the distinction between how a brand organizes its products, services and offerings (brand architecture) and how it organizes its web pages (information architecture). It’s easy to see how there might be confusion. After all, since both are customer-facing, shouldn’t a website’s information architecture reflect the brand architecture and vice versa? If the two systems have similar goals, why separate them?

Too often, companies assume that B2B brand architecture and information architecture can be collapsed—most often with the latter serving as the former. This is especially apparent after a rebrand, when a company jumps into website design without having properly addressed brand architecture.

This can be a costly mistake, however, and diminish the value that the rebrand can create. Out in the market, there can be a lack of consensus, or even understanding, of the offerings associated with brands and sub-brands in the company’s portfolio.

Brand and information architecture are related, but one can’t be substituted for the other. It’s helpful to start by defining both and thinking about the roles they perform for the business.

What is Brand Architecture?

Brand architecture is the structure of brands and sub-brands within an organizational entity. It defines the hierarchy, relationships and differentiation among brands in a portfolio.

The goal of brand architecture is to find the system that best supports the business strategy and brand goals. Examples of objectives that brand architecture can support include empowering cross-selling or elevating fast-growth, high potential products and services.

A good B2B brand architecture helps streamline how the company’s portfolio of brands are named (co-branded, endorsed, etc.) and identified (logo, typography, etc.). It also provides a roadmap for future acquisition naming. Most importantly, it is a communication tool that helps shape internal and external audiences’ understanding of what the company does and how someone should interact with its brands.

What is Information Architecture?

Information architecture organizes, structures and labels content on a website in an effective and sustainable way for the end user. Website design centers around the end user and their goals for their time on the site. As part of the company’s greater digital brand strategy, information architecture is all about optimizing usability: making the information that’s most important to your audiences easy to find.

Often, a website offers many entry points for how visitors can get information, such as region, product, vertical or customer type. If you’re a prospect of a global company operating in Europe, you want to look up information based on your location, as information for North America is not relevant to you. You may want to go directly to the product you’re interested in. Or, you might want to learn about all of the products and services within your vertical market. Whatever the case, you’ll want to find the information you are looking for as quickly as possible, and smart information architecture enables this.

To compare brand architecture and information architecture, consider FedEx. Its sub-brands include FedEx Ground, FedEx Express, FedEx Freight and FedEx Office. But while this is how employees, shareholders, and analysts may think of the divisions within the company, it’s not how a customer does. These business units reflect corporate strategy and operations. They don’t speak to individual shopper needs.

Put plainly, the FedEx customer knows they want to overnight a lamp; they don’t really care if that’s accomplished by Ground, Express or Freight services. To reflect this, FedEx.com’s information is not organized by sub-brand but by customer need state, such as “shipping,” “tracking” and “printing.”

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

When They Can Be the Same

B2B brand architecture and information architecture often overlap, sometimes very closely. This is especially true for companies with fewer brands, products or services. For example, in a master brand architecture strategy (where each product or service is named after and organized under the corporate brand), a company might be able to get away with the same website organization as its brand portfolio.

However, instances when the information architecture of the website mirrors the exact organization and structure of products or services in a company’s portfolio is rare. Leaders should not consider this relationship the default in their haste to get a new website published after a rebrand.

When They are Different

Even if a company’s offerings line up with how information might be organized on its website, it doesn’t mean that the company’s brand architecture is the same as its information architecture. On one hand, end user needs may dictate that the website offer several different ways to access certain types of information. There are also operational considerations. If the website is meant to serve as a lead generation platform, that can have important implications for information architecture without impacting brand architecture.

On the other end of the spectrum, the brand may have so many properties, such as in a house-of-brands architecture, that it would be inordinately chaotic to try to include all of the products and their related pages on one master website.

Lastly, there may be website content that isn’t part of the brand architecture, such as whitepapers, events, careers and investor information. While there are definitely branded offerings that could also be present on the corporate brand architecture (such as a branded corporate social responsibility program), there are many more content types that are web-only.

Like brand architecture, information architecture is an important communication tool. But one with a singular purpose: to serve visitors of a website. Yes, the website is an expression of the brand, but it has a very specific list of functions. And therein lies the fundamental difference: brand architecture is driven primarily by the goals and needs of a firm’s business and brand; information architecture is driven primarily by the goals and needs of the website’s end users.

How to Determine Your Approach

User experience research is key to establishing the ideal brand architecture and information architecture. It helps leaders understand how customers think about what they’re buying, where they expect to find information about it, and how they prefer to learn. Interviews often reveal key motivations and considerations, and rapid prototyping is a useful tool for identifying user experience preferences (which may be harder for customers to articulate).

From such research, leaders typically learn that while each type of architecture should inform the other, one won’t define the other. They are separate but equally important. And when built strategically, both help simplify and communicate information, making it easier for clients, prospects, employees, investors and other audiences to understand and interact with the business.

The desire to jump right into website design following a B2B rebrand is understandable. Everyone wants to make the right first impression, and today, those impressions are made online. But B2B marketers who take the time to conduct thoughtful research and think through their brand and information architecture will benefit. They’ll have a clearer and more consistent understanding their audiences and how the company can meet its audiences where they are. And with a website built from well-informed digital strategy, they’ll gain a streamlined platform for achieving business and brand goals.

Want to talk about optimizing your brand and information architecture? Let’s talk.

Originally published October 17, 2021.