Mission, vision, values: if you’re of a certain age, when you hear these terms you might feel transported back to the ’80s or ’90s, to the height of the “planning school” and corporate jargon. In 1984, one influential business writer proclaimed, “everyone agrees they are necessary”—and the stats backed this up. In 1991, 70 percent of respondents to a survey of top companies reported crafting a mission statement in the past four years.

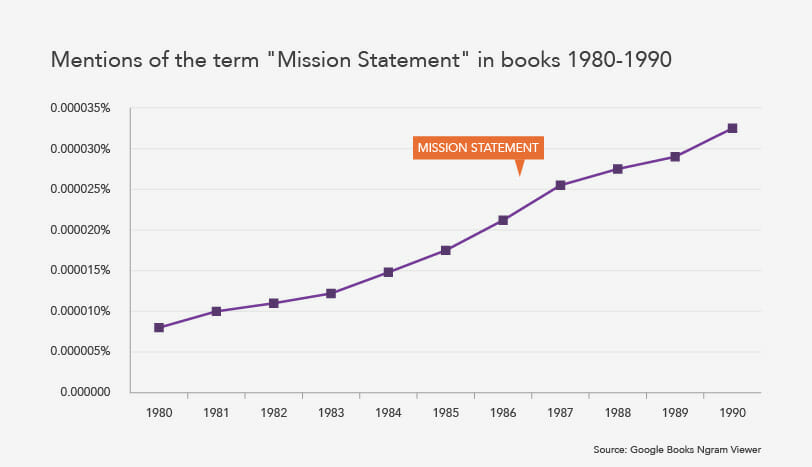

Using Google’s Ngram viewer, we tracked the term “mission statement” in books and found it increased over 285 percent between 1980 and 1990.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

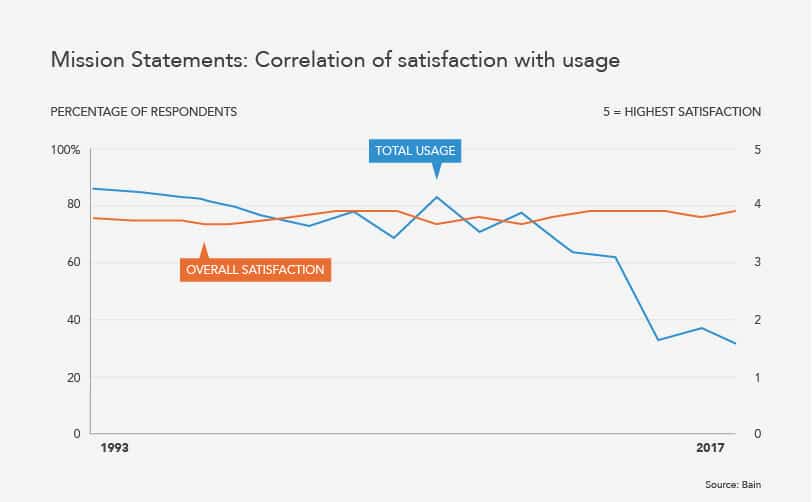

However, sometime in the late ’90s and early ’00s, the popularity of corporate mission statements began to plummet. Research from Bain shows that from its peak in 1993 at 85 percent, the percentage of companies using mission statements dropped to 30 percent by 2017.

Why the change?

Organizational results were mixed. Research showed that the mere existence of a mission statement did not have a strong correlation with improved financial performance—but that strong mission statements did. Some companies, in their haste to create corporate mission documents, ended up with statements that did not resonate with their audiences or could not stand the test of time.

These rushed company mission statements often shared at least one of three fatal issues, as outlined by Inés Alegre in the Journal of Management and Organization:

The 3 Attributes of Failed Corporate Mission Statements

1. They were delegated to subordinates by disinterested executives

Alegre notes that in the ’80s and ’90s, the common approach to mission statement formulation was for top management to delegate the initial drafting to their subordinates and then review subsequent drafts until the CEO was satisfied. This method was time-consuming and did not provide the greater team involvement necessary to permeate the mission throughout the organization.

In an attempt to work more efficiently through delegation, these companies often spent more time revising drafts than they would have creating a proper, collaborative mission statement from the get-go.

2. They were the only documents summarizing organizational strategy for employees

Without enriching materials, programs and events, and without complementary initiatives like purpose, vision, and values, mission statements don’t pack much of a punch. To create value, they must be frequently and consistently reiterated, exemplified and modeled.

Offering employees only one way to consider your “Why” is likely to be ineffective—particularly when such a statement is packed with buzzwords and “corporate-speak,” as the first mission statements often were. Think of how we all have unique learning styles. While a formal mission statement may connect with some employees, others may have their “Aha” moment relating to corporate values or a set of shared behaviors, a CEO speech, or a brand film about employee engagement.

3. They were static documents that didn’t reflect their company’s changing world

We’ve heard it trumpeted again and again: our world is moving fast. So it’s difficult to write a mission statement that feels relevant for 10 (or even five) years. But while specific performance goals may date a statement too quickly, erring on the side of vagueness may also abstract the statement from employees’ everyday worlds. It’s a tricky balance between static and soft. But it’s vital that companies try to find it.

Bain’s research supports the idea that those who thoughtfully planned their purpose, mission, vision and values (PMVV) work saw results. Although the early ’00s saw a steep drop-off in companies using mission statements, satisfaction rates remained high. Extrapolating, one can posit that those who didn’t see results simply abandoned their projects, while those whose good work produced results persisted with their PMVV initiatives.

However, it seems like the PMVV bloodletting has finally stopped. What’s old is new again. Recently, branding professionals have been fielding more and more requests for PMVV deliverables. While brand and purpose are distinct, companies recognize that by linking them closely, one can more effectively cascade purpose through strategy, HR, operations and marketing.

Why the shift back toward PMVV? Context and cohorts.

First the context. In many ways, our socioeconomic climate is similar to that of the early ’80s, when the mission statement hit the market. We’re rebounding from an economic crash, like we were after the gas crises of the ’70s. We have significant political insecurity both at home and abroad, like that faced during the Cold War. Our population is remarkably divided, like we were during the “culture wars” of the ’80s and ’90s. The idea of an initiative that promotes workplace unity and prosperity is appealing.

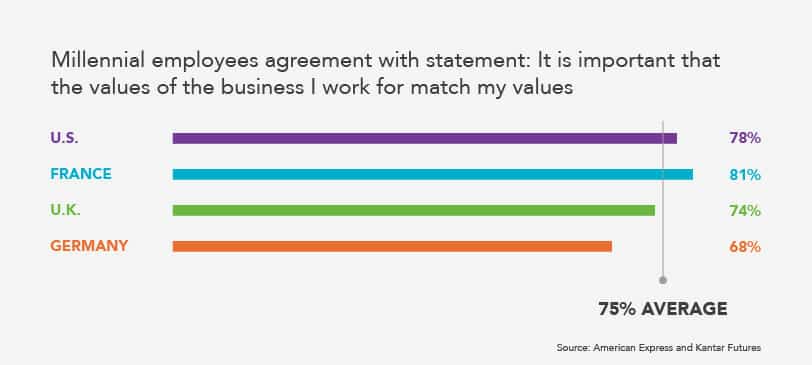

This context has produced a cohort, a generation, that is strongly driven by mission and purpose in both its professional and private lives. Of course, we’re talking about the much-examined Millennials, now in leadership positions across industries. In one survey by American Express, 81 percent of American Millennials reported that a successful business needs to have a genuine purpose, and 78 percent said the values of their employer should match their own.

Rising Gen Z is also known for their preference for purpose in their work lives. According to research from Porter Novell/Cone, 83 percent of Gen Z respondents reported that they consider a company’s purpose when deciding where to work.

So, the time is right to take a second look at mission and purpose statements, corporate visions and values, and the like. But it’s critical not to repeat the mistakes of prior decades. To ensure success, PMVV work needs to be carefully planned, collaborative and consistently emphasized.

Purpose, Mission, Vision, Values 101

A lot of terms get thrown around in discussions of corporate mission statements, brand purpose, and core brand values. Too often, these terms are used interchangeably—or, worse, to refer to brand strategy deliverables such as positioning. Here’s a brief primer of terms you need to know and what you need to do relative to them.

Brand Experience Principles

Sometimes known as brand behavior or brand principles, these guidelines define how the company interacts across touchpoints, physical and digital. To maximize value creation, leaders have to operationalize the company’s mission, vision, values and purpose for employees by giving them clear directions on how to implement them in their outlooks and in their day-to-day work—and this is what brand experience principles provide.

This well-known set of brand experience principles once defined Facebook (pre-2014):

- Move fast and break things

- Do not let a competitor get ahead of you

- Adhere to the process

- Create an exciting workplace

The “Big, Hairy, Audacious Goal” (BHAG)

This is a far-in-the-future goal that may change the very nature of a company’s business. Here’s GE’s version:

- To become #1 or #2 in every market we serve and revolutionize this company to have the speed and agility of a small enterprise

Brand Promise

Your brand promise is the experience or value that a customer can expect to have at each of a brand’s touchpoints; the term is also closely related to customer experience design. REI’s brand promise is a good example:

- Bringing the outdoors into the retail experience

Mission

Your mission is a statement that describes the company’s business and operational goals now and in the near-term, and it is designed to focus on leadership and employees. It can also provide a clear explanation of what the business is and isn’t. Consider Warby Parker’s:

- Warby Parker was founded with a rebellious spirit and a lofty objective: to offer designer eyewear at a revolutionary price, while leading the way for socially conscious businesses

Purpose

Your purpose is your ultimate “Why”: the reason your company exists for external audiences—notably customers and the world at large. It should be written from an external perspective, placing employees in the shoes of buyers and community-members. Here’s an example from EY:

- Building a better working world

Values

Your values are your organization’s core beliefs, defining the company’s culture and guiding leadership’s decision making. Here are a memorable set of values from Swedish shipping line Maersk, notably grounded in humbleness:

- Listen, learn, share and give space to others

- Showing trust and giving empowerment

- Having an attitude of continuous learning

- Never underestimating our competitors or other stakeholders

- Acknowledging our limits and mistakes

Vision

Often articulated by company leadership, your vision lays out what the company wants to achieve in the future, usually several years down the road. EY has a nice example of brand vision:

- By 2020, we will be a US$50 billion distinctive professional services organization

Focus on Brand Purpose

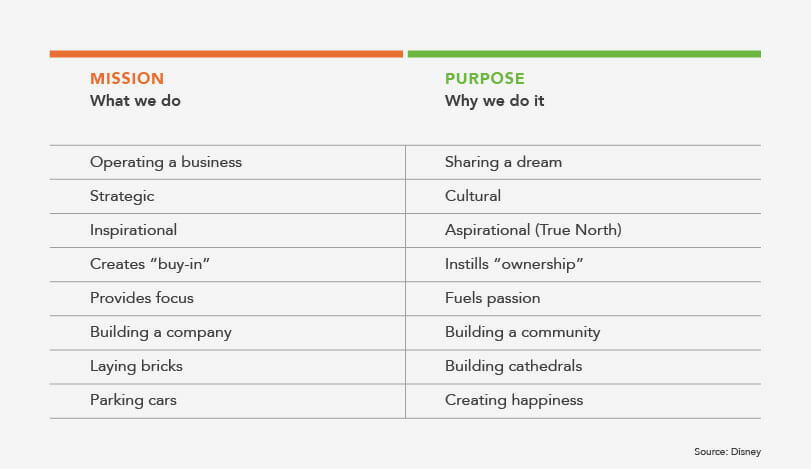

If you take anything from this list of terms and examples, let it be this: purpose and mission are different. Mission is what you come to work every day to achieve, but purpose is why what you do matters for the world. This means that in terms of your brand, purpose is where your attention should be focused first.

Here’s a great example of this from Disney:

This isn’t to say that internal perspectives aren’t important; they are. However, in Harvard Business Review, Graham Kenny writes that not only are customer-centric purpose statements more resonant with customers, they are also more effective in rallying employees, as they “connect with the heart as well as the head.”

Focusing on purpose doesn’t mean ignoring other traditional brand mission, vision and values initiatives. It just means understanding that all of these ladder up to purpose. Values enrich the brand mission and vision, which in turn support and operationalize brand purpose.

Eager to get started? Here are four steps to building a resonant, enduring brand purpose.

How to Build Your Brand Purpose

1. Invest in employee engagement

Creating your brand’s purpose, mission, vision and values in a vacuum drastically increases the chances they will fall flat and fail to resonate. Andrew Marty, a psychologist turned human resources consultant, points to research that shows that in corporations, 85 percent of an individual employee’s sense of well-being comes from their local teams and day-to-day experiences, while only 15 percent comes from organization-wide policies. This suggests that for an organizational brand purpose to resonate with employees, they must see their team’s roles reflected in it.

Employees need to be able to envision how the business’s purpose, mission, visio, and values apply to their day-to-day lives. Ideally, they will have a part in the PMVV process. But if not, they need to understand and buy into it.

A true bottom-up approach to brand purpose includes employees through input sessions and feedback loops. They could take the form of company-wide surveys, departmental workshops or town halls. Employee involvement shouldn’t stop when the document is created, either. Ongoing employee engagement programs are necessary to spread and maintain awareness of how purpose is relevant to individuals, as well as to gauge whether refinements are needed as contexts shift.

On an ongoing basis, employee engagement can and should take multiple forms: environmental branding, training, ambassador programs, and awards programs are just a few tactics.

2. Show enthusiastic executive modeling

Employee involvement is vital, but it’s hard to secure it without a visible and compelling commitment from executives. Brand purpose work can’t look like it is the purview of HR or marketing; it needs to be clear it is an organization-wide initiative, dependent on everyone’s participation.

One of the most powerful symbols of change is a CEO who champions it. The CEO, and other executives, should make a point of introducing and endorsing the initiative, its day-to-day project leaders, and its results. This will help assuage concerns that brand purpose is an empty promise and it will encourage active participation across the organization.

In addition to being active in the project’s roll out, leadership needs to show how it affects even boardroom behavior. This modeling could take the form of more regular communications, leadership blogging, purpose roadshows, or even operational changes such as updated compensation schemes or reporting structures.

Maersk does a great job emphasizing its leadership’s stalwart belief in its corporate values. The company prominently displayed richly produced videos of the Möller-Maersk family musing on the importance of its uniquely Scandinavian values—and enriched leadership’s stories with videos of everyday employees speaking about the same corporate beliefs.

3. Strive to stand out

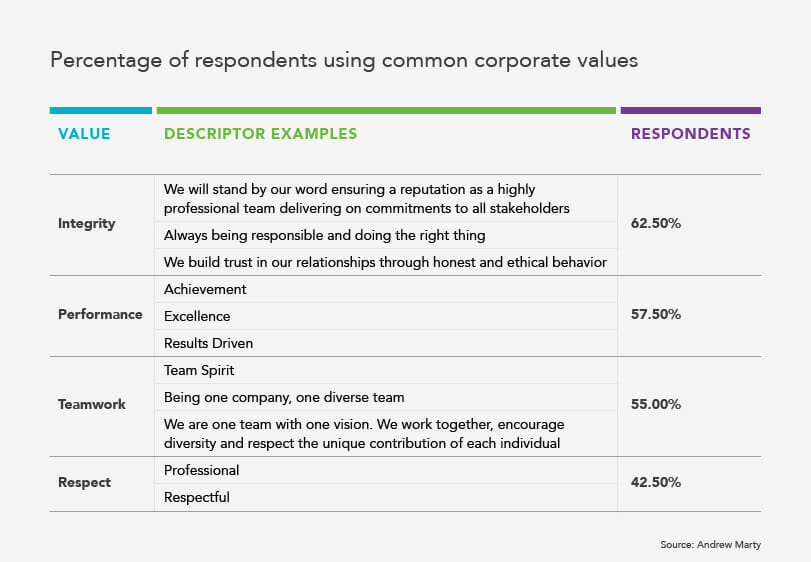

One of the reasons that brand purpose, mission, vision and values get a bad rap is because too many companies have used them as corporate hygiene instead of as a differentiator. Marty’s informal study of brand values in a group of 40 companies shows that, for example, 62.5 percent of companies include integrity and 57.5 percent include performance.

This is no place to affirm table stakes. Ideally, customers and stakeholders expect your company to be responsible, collaborative, and profitable. Instead, this is an opportunity to highlight what differentiates your culture and strategy. Not only should your high-level concepts be unique, you also should express them using clear and “human” language. Nothing sparks skepticism like words such as “synergies” or “disruption.”

SquareSpace’s values are a good example of values that deviate from the norm—in a good way. With just a few words, they give the reader an impression of what it’s like to work with or for the organization:

- Be your own customer

- Empower individuals

- Design is not a luxury

- Good work takes time

- Optimize towards ideals

- Simplify

4. Build your brand purpose, mission, vision and values to flex

Academic research on mission statements of the ’80s and ’90s found that many were too static—leading to them quickly feeling stale and irrelevant to employees and customers. By making purpose the hero (rather than mission or vision), a company can mitigate some of the risk that comes from focusing too heavily on of-the-moment metrics or processes. Nonetheless, a conscious effort should be made to “future proof” visioning documents so they can continue to guide and inspire for many years to come.

“Future proofing” means both careful consideration and pragmatic iteration. Of course, efforts should be made to write something that is simultaneously timely and timeless. But since this is all but an impossibility, resources should be created and shared in ways that allow for—and even encourage—incremental change. This means both their structure and their medium should be built to flex, something that might be necessary after M&A, market changes, divestment, employee feedback, or (with luck) after goals have been achieved!

Remember, in our digital world, writing and designing for change is easier and more important than ever. So always consider: How can documents be formatted for seamless editing? How can they be disseminated and promoted in adaptable ways?

The takeaway? Your brand purpose, mission, vision and values play an increasingly vital role engaging employees and building brand esteem and equity in the market. With purpose-driven generations flooding the workforce (working both with you and for you), and decades of validation for the strategy, clarifying your “Why” will remain vitally important moving forward.

Want to discuss how a clear brand purpose can drive value creation for your organization? Let’s talk.

Originally published January 18, 2020.